A few simple, proactive steps will help reduce the chance of this terrible event from occurring on your watch.

I recently attended a large public event hacked by someone making racist, sexist, homophobic remarks. It was the kind of event that it was obvious would attract people who identify as belonging to one or more underrepresented groups. This audience made it the perfect target for people who believe members of these underrepresented groups have no value. This was the second event I attended in the past two months that had been hacked in this way. I continue to be disturbed by the statements made by the event hackers to this day.

I had been looking forward to this event for weeks

Instead, I listened to the second half with a somewhat numb, and heavy heart.

Being on an event where ad hominem, racist, ableist, homophobic, or misogynistic attacks occur is a harrowing experience for your participants, even if not all of your participants don’t identify with the groups that are being attacked. The bell can’t be unrung. No amount of apologizing removes the damage of the attack.

I’m not technical. What can I do?

If you are hosting an event, it is on YOU to determine your level of risk to have one of these individuals attending and craft an event that makes it as difficult as possible to have a platform for their discriminatory agenda.

If your event is open to the public, and your topic includes disability, gender, LGBTQIA2+, civil rights, politics, or anti-racism the risk is unfortunately close to 100 % of one of your events someday getting hacked if you do not take proactive preventative steps.

Evil people are out there. We (the public) rely on you (the event holder) to keep these people out. In this case, the boogeyman is real.

My hints below are for how to meet those responsibilities in an accessible manner. Because I am first and foremost, an accessibility professional, I have also provided accessibility hints to the security suggestions.

Making digital things “more secure”

frequently results in making them harder to use

for people who use assistive technology.

You don’t want to create barriers for people with disabilities to attend your events just because your event may have a boogeyman.

1. Use a strong event password.

Security: Using strong event passwords is the first step in tightening up event security.

Accessibility: Make sure the password is embedded in the link within the event invitation. It is difficult and time-consuming for people with vision loss to find the password in the invite when the “Hey, what’s the password” dialog comes up after the link is clicked.

2. Require event registration.

Security: By requiring event registration, you can validate that email accounts or cell phones exist before accepting someone’s registration. This approach additionally allows you to request the “real name” of the event registrant, with the caveat that people register using fake names all the time. Look for apparent lies like “Fred Flintstone” and “Mickey Mouse” in your attendees’ list and scrutinize those individuals closely.

Accessibility: Make sure you follow basic accessibility requirements for form construction.

- Form infrastructure must be accessible. The only form/survey builders I ever use are MS Forms, Google Forms, Survey Monkey, and Qualtrics. Each of these can build a 100 % accessible form. Anything else at the moment, all bets are off.

- Form content and error behavior must be accessible. Review your form for the use of color, legends, field grouping, and signal that a field is mandatory. Ensure all field restrictions are announced by the screen reader when the person enters the field (or before it) and not only after. Check your error messaging against WCAG guidelines.

- Don’t use inaccessible CAPTCHAs on your form under ANY circumstances. If you feel you need a CAPTCHA, investigate using honeypots. If you must use a CAPTCHA, use the Google I am not a Robot reCAPTCHA v3.

3. Don’t send the link too early, and never EVER put the link somewhere that is searchable by public search engines.

Security: Don’t send out the link to the event until a couple of days before the event. Initially, if the event is more than a couple of days out, send a placeholder summarizing the event instead of a link to block the person’s calendar. Tell the participant in the invite that an individualized link will be provided the day before the event and ask people not to share to make the environment more secure. People are less likely to post/share links if they know they are tied back to the registered individual.

4. Never EVER reuse links for public meetings.

Security: The more you reuse a link, the more likely someone will post it, or it will get randomly derived by people trying to brute-force crack the encryption for your password. Use your static “room” URL for quick internal private chats, but generate new links for any meetings where the general public is invited.

5. Have a portal for questions to be submitted and filtered in advance.

Security: Opening up the meeting for questions can be problematic.

- If you have a Q&A section, hate speech can be posted there but quickly deleted. Remember to identify the person responsible so you can kick them off before the message has been deleted.

- If you open up microphones with an unknown public audience, you have no idea what you will get.

Asking for questions in advance is one way of avoiding these situations.

Accessibility: Same accessibility rules apply to questions submission portals like the ones identified in Event Registration in step #2 above.

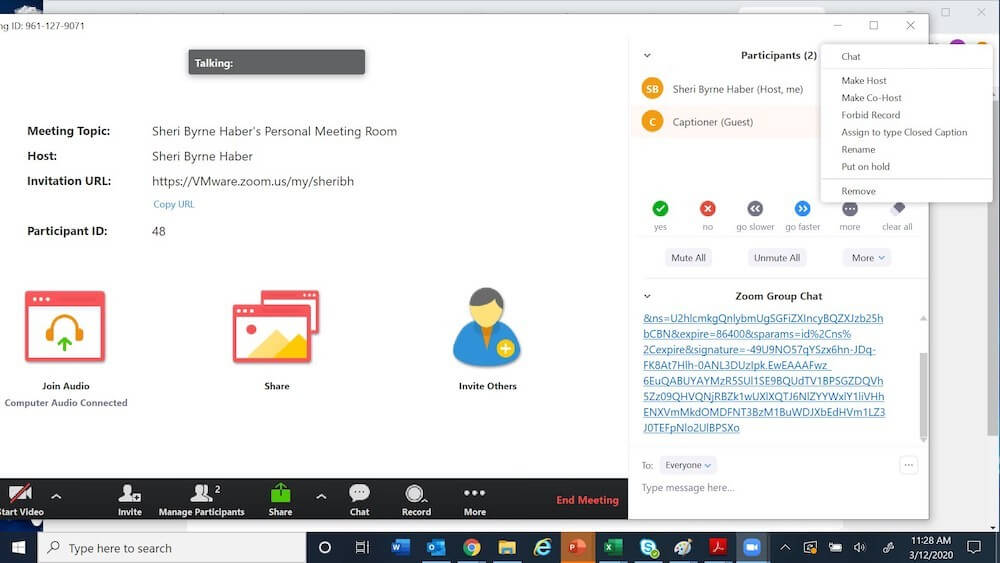

6. Use a conference tool that supports waiting rooms.

Security: The Waiting Room feature allows the event host to control when a participant joins the meeting. As the meeting host, you can admit attendees one by one or hold all attendees in the waiting room and admit them all at once. The latter is useful when you have a large panel of individuals speaking and want to gather them in a separate room until the event begins.

7. Use a paid webinar feature.

Security: Unfortunately, most conferencing software starts as freeware, and advanced features have to be purchased. By paying for a webinar feature, you can automatically:

- Suppress chat windows.

- Keep everyone’s microphones turned off, except for panelists.

- Do not allow participants to turn on video.

Accessibility: If you use zoom with the paid webinar, you can more easily caption. If captioning is required but you can’t afford paid zoom or paid captioning, use MS Teams or Google Meets instead — both have a free auto-captioning engine.

8. Have “in case of hack, break glass” cookbook

Security: Don’t be so shocked you freeze when you get hacked. If you prepare for a hack like it is an eventuality and do “hack drills” with the people running the event, you will be more likely to end up with the best possible outcome under the circumstances.

- Have someone on “hot standby” (effectively a silent facilitator) who has no other responsibilities and knows how to clear the chat, delete questions, mute people, and kick people off. Think of them as the video conference equivalent of the person on the 7-second “curse” button at a live radio station that takes phone calls from the general public.

- Have a step-by-step process that describes what you do if the event gets hacked. You may want to change the link and update the invite, for example, if you have a relatively small number of attendees, or reschedule the event if you have a larger number of attendees. For large, paid events, you REALLY need to have a plan. People are slightly more forgiving of unpaid events getting hacked — all the people involved with running those events are effectively volunteers. Not so much for paid events that get hacked.

- Prepare a statement describing the hack, apologize to the attendees, and talk about what you will do in the future to prevent this from recurring. Including that in your message will help folks traumatized by the hack to trust future events. Send a personalized email from your organization to the attendees, and post a general comment on your website or official social media channels — you don’t want the rumor mill controlling the messaging here. And you want to make it clear you won’t be as soft of a target next time to the evil-doers.

- Are you going to involve the police/FBI? Take a screenshot, so you have evidence and identify attendees both inside and outside of your organization who are willing to attest to what happened without increasing their trauma.

Accessibility:

- Make sure the statements themselves are accessible.

- If you are going to change the link mid-event or reschedule, make sure people with disabilities know what’s going on.

Please, please, please do some or even all of these things as they apply to you. Don’t EVER give hateful individuals an easy portal to spew their hateful messages.

Not that long ago, we weren’t required to go through metal detectors to go to court, and we didn’t have to have our shoes examined by the TSA to get on an airplane. Bluntly, we do NOT live in that society anymore. People abusing others’ zoom meetings to share their spiteful beliefs is just the latest misuse of new technology. We need to protect underrepresented groups from being further traumatized from allowing people to hack our events.

0 comments on “How to prevent your conference calls from getting hacked”